| Recent Lab Papers | Synopsis |

|

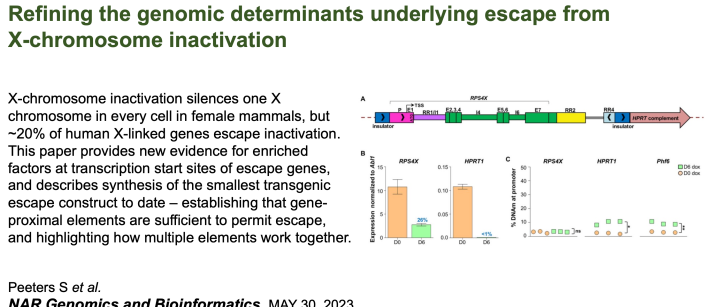

Sam has reduced the elements that allow a human gene to escape from X inactivation to under 6 kb! |

|

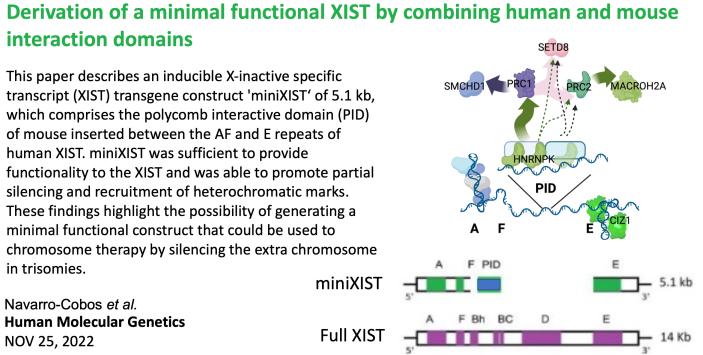

In mice a small region of the B/C repeats is critical for PRC1 and subsequent PRC2 recruitment. Combining other critical domains (see Tom’s work below) with this mouse ‘PID” Maria Jose asked if she could make a small functional XIST. Surprisingly, addition of PID helped both silencing and heterochromatin – but only halfway… more studies underway, but read this one here. |

|

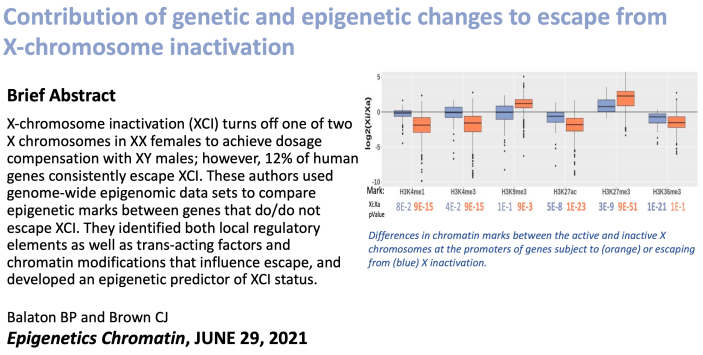

Brad examined which features best differentiate the genes that are subject to X inactivation from those that escape silencing. Click the image to read the paper. |

|

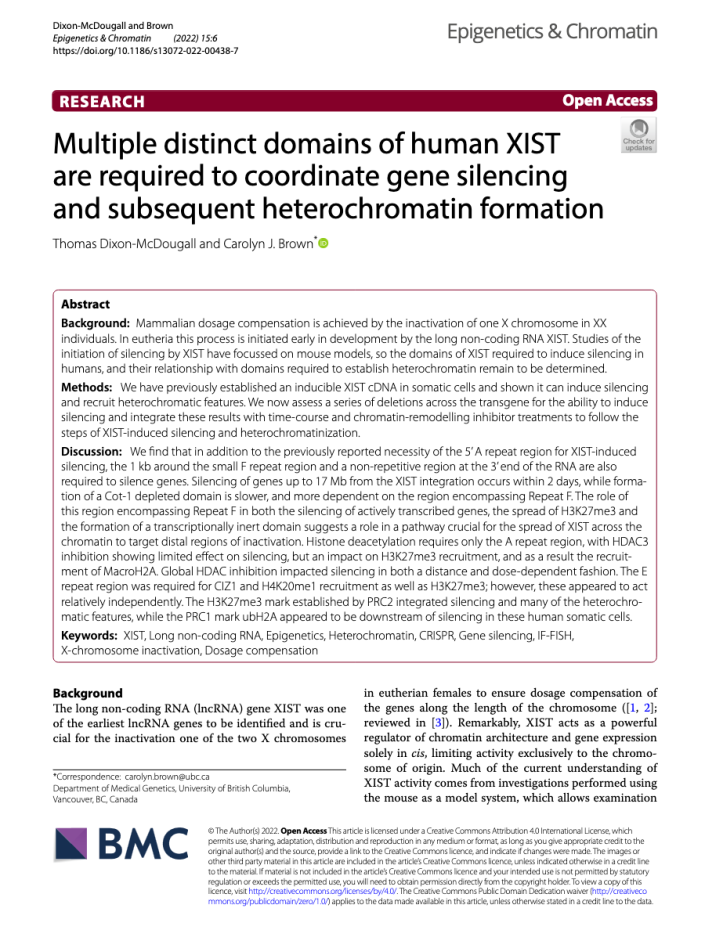

Tom used his series of deletions to further demonstrate that silencing by XIST needed multiple regions of the XIST RNA – this paper is here. |

|

In humans a startling 20-25% of genes ‘escape’ inactivation. In this paper Brad ‘mined’ existing transcriptomic and DNA methylation resources to examine which genes escape inactivation in other species. While mice have few escape genes, other mammals are more similar to humans. Many of the escape genes are the same across species – and they often occur in blocks. |

|

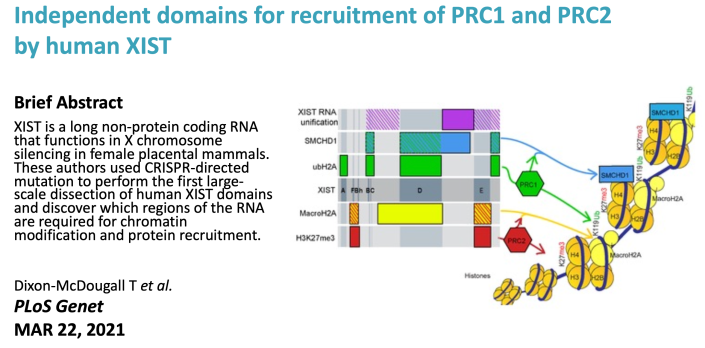

Thomas made a panel of deletions using CRISPR that span the inducible XIST transgene. Examining these for multiple chromatin marks associated with the inactive X revealed that in these cells PRC1 and PRC1 recruitment relies on different domains and not each other. See the paper here. |

This review is part of a special issue |

X chromosome aneuploidy (a gain or loss of a chromosome) can be tolerated for the X chromosome due to inactivation normally compensating for the dosage of X-linked genes. Males with two X chromosomes as well as the Y chromosome (XXY) inactivate one X, similar to females. While this minimizes the impact of the aneuploidy, the genes that escape inactivation likely contribute to the phenotype associated with the XXY Klinefelter syndrome. |

Find the paper here |

Using the transgenic mice that incorporated the human ‘escapee’ RPS4X on the mouse X chromosome, Sam demonstrated that escape from inactivation was stable – occurring early and lasting up to a year. |

The review is part of a series on X inactivation |

The X-linked genes that retain Y homology are more likely to escape from inactivation. In this review, Bronwyn discusses the evolutionary history of genes that escape inactivation. |

The paper is available from PLOS ONE |

Long non-coding RNAs such as XIST can also interact with other RNAs – and thus might ‘absorb’ or ‘sponge’ up small regulatory RNAs like miRNAs. But because they are long, sequence alone will predict many interactions; in this collaborative paper with Erin and colleagues in the Lam laboratory, additional features such as sex and nuclear location were considered to refine the list of potentially interacting miRNAs. |

|

In pursuit of “DNA elements” that control whether a gene will escape from X-chromosome inactivation, in this paper Sam collaborated with the Simpson lab at CMMT to integrate about 150 kb of human DNA into the mouse X. This DNA included a gene that escapes silencing in humans (but the mouse gene is subject to X inactivation) and a flanking subject gene. This expression pattern was also observed in the mice, suggesting the ‘escape element’ is within the DNA, and recognized by mouse. |

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27103486 |

12-20% of human genes escape inactivation and continue to be expressed from the otherwise inactive X chromosome. These exceptions to silencing can inform our understanding of the silencing process, and are also differentially expressed between males and females, so may be important contributors to sexually dimorphic disease predispositions. In this review we tabulate the differences in epigenetic marks between the escape and subject genes, review how escape genes have been identified, and describe recent results about the nuclear ultrastructure of the inactive X chromosome. |

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26849907 |

X-chromosome inactivation is generally a random choice of one or the other X to inactivate, resulting in females being mosaics of cells with each X active (the Calico Cat is our usual example).

But inactivation is not always random – and skewing is important for modulating the disease severity of female carriers of X-linked disease. Therefore we would like to understand how skewing occurs. Humans and mice both undergo X-chromosome inactivation; but there are important differences between the two species, and in this review we discuss whether there is a region controlling skewing of inactivation in humans, as there is in mice. |

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26429547 |

We have previously shown that induction of XIST in a human somatic cell can result in localization of the RNA and recruitment of some features of an inactive X.

In this study we have put the inducible XIST into 9 different places in the human genome and while they all localize XIST, the site of integration impacts how well silencing can be established. Silencing can skip over regions, and seems to favour places that already have some pre-existing H3K27me3. All sites recruited H2A ubiquitinylation and showed a shift to the perinuclear periphery upon XIST induction. |

http://wwww.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25381334 |

DNA methylation is found at the CpG island promoters of X-linked genes subject to X-chromosome inactivation. In order to identify genes that are subject to inactivation we have surveyed datasets from 27 different tissues to compare male (who only have an active X) and female (who have an inactive X in addition to the active X) levels of DNA methylation.

The level of DNA methylation is very consistent across tissues, and we see a very strong inverse correlation with expression at the promoter, and a smaller correlation in the gene body, allowing us to ‘call’ more escape genes. In summary:

|

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25200388 |

Expression of the XIST gene initiates X-chromosome inactivation. But what flips the XIST switch? In mice there is an antisense to XIST that regulates XIST expression, but the region around XIST is very different between humans and mice. Yet both humans and mice have a second major promoter “P2” embedded within the gene. Surprisingly P2 would not create a functional XIST RNA as it is downstream of the critical “A repeats” that are essential for silencing. Could P2 be a common regulator of XIST/Xist? We show that P2 is located in a differentially methylated set of YY1 binding sites and that YY1 is critical for XIST expression and localization |

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24158853 |

X-chromosome inactivation can spread into DNA that is adjacent to the XIST gene, even if that DNA is an autosome translocated to the X. We examined the spread of inactivation into the autosomal DNA in unbalanced X/autosome translocations using DNA methylation to identify silenced genes. The spread of silencing on the autosome was less complete than on the X chromosome, consistent with the 1983 proposal by Riggs and Gartler of ‘waystations’ that are more abundant on the X than other chromosomes. We show that spread is entriched at regions with pre-existing EZH2 or other heterochromatic marks, while escape from silencing is best correlated with the presence of ALU repeat elements. |

| Collaborative Studies | Description |

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27857184 |

In silico analyses of FANTOM5 CAGE data was used to identify genes showing sex differences in expression levels. Those genes that are likely to escape X-chromosome inactivation were further shown to be over-represented for the transcription factor YY1 in ChIP-seq data, and show YY1 motif over-representation compared to autosomal genes or genes subject to inactivation. |

|

The Lawrence laboratory at U. Massachusetts are expert cell biologists who were the first to visualize XIST in the nucleus.

Here, they are the first to approach the idea of ‘chromosome therapy’ – that if XIST silences in cis, then integration of XIST will ‘correct’ a trisomy by silencing the extra copy. XIST was able to silence a chromosome 21 in Down’s syndrome iPS cells – really well, according to DNA methylation! |

|

We have collaborated with the Lam laboratory on many studies looking at DNA methylation – but additional roles for RNAs in controlling aberrant gene expression in cancer cells is a new avenue that Victor pursued. |

|

The Robinson lab are also long-time collaborators. Here Magda and Allison got together to create an annotation of the 450K DNA methylation array. |